Craig Grannell wants to paint a big arrow that points to a picture of an arrow, telling Apple: do this

I spend most of my day sitting in front of my iMac. It’s a great computer, but I’d prefer to spend more time sitting in front of my iPad. Apple’s sleek tablet is lightweight, portable, and forces focus, mostly displaying a single app. The problem is that it’s not geared towards long-term tasks that involve a lot of working with words – and as a writer, working with words is what I do.

Sure, you can snap the iPad into Apple’s Smart Keyboard Folio, or any number of third-party equivalents that transform the tablet into a sort-of laptop. But then you end up with the same ergonomic problems laptops give you while hunched over the screen. It’s a fast track to Bad Back City. And because iOS lacks pointer support, you must too often interact directly with the display, which becomes tiring – and tiresome.

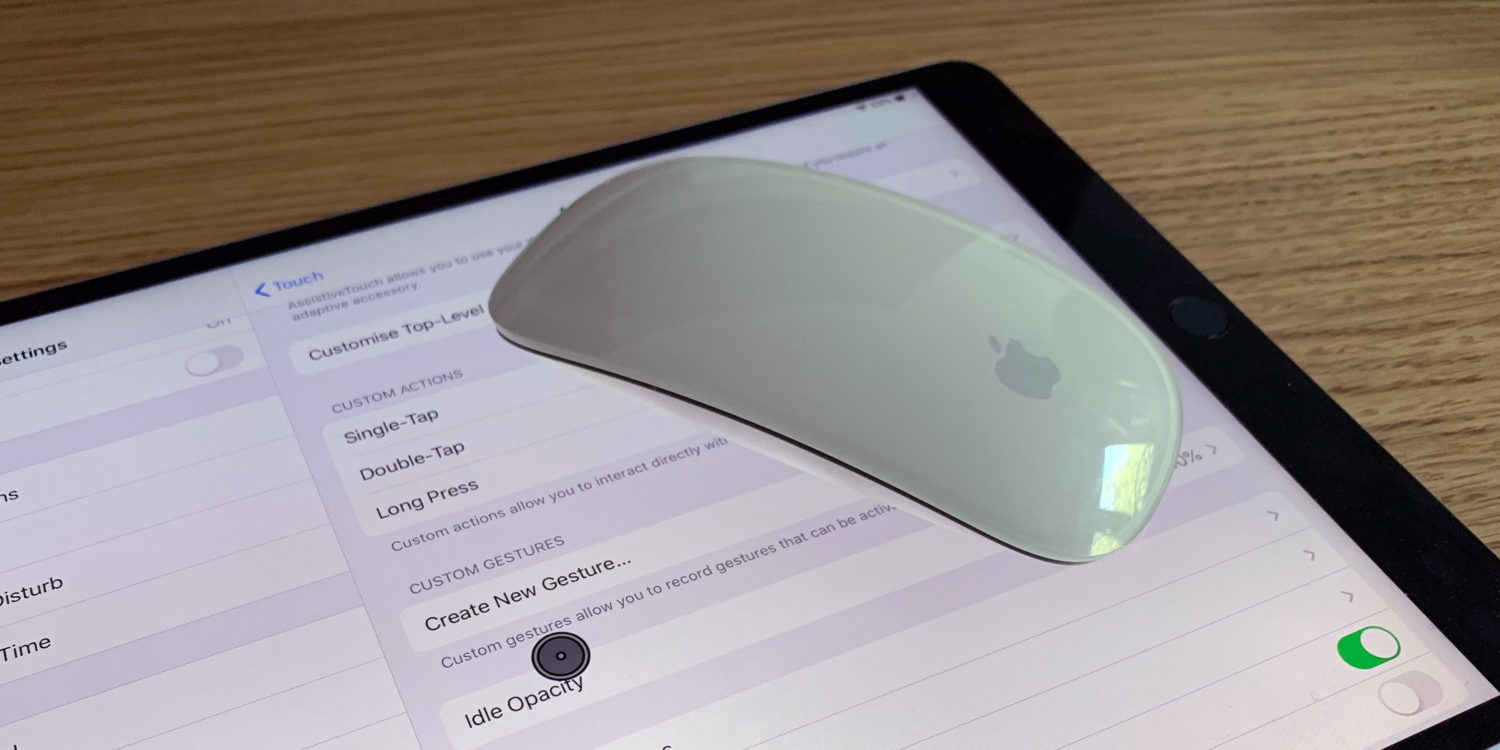

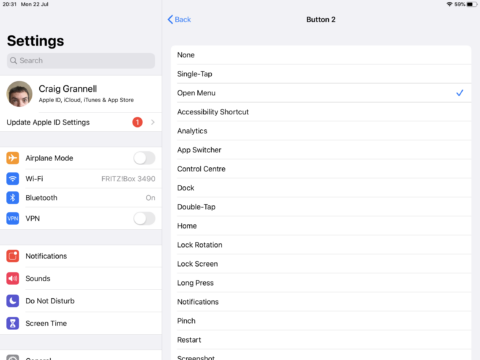

Plug a mouse into an iPad running the iOS 13 beta, and you can fire up AssistiveTouch in the new Accessibility section in Settings. As of the most recent public beta, the comically large disc-based pointer that once appeared when you plugged in a mouse is now of saner dimensions. Even so, this isn’t the holy grail for people who in specific use-cases want the iPad to work more like a traditional computer.

With AssistiveTouch’s mouse mode, you gain the benefits of precision when interacting with fiddly on-screen elements like text and spreadsheet cells, and in being able to assign actions (like returning to the Home screen) to various mouse buttons. But the circular pointer’s pretending to be a finger, not a desktop-like cursor. This means interactions don’t align with what you’d expect when using this kind of input mechanism. Selecting text remains a slothful experience; the AssistiveTouch menu always remaining on-screen is a distraction.

If we had a cursor, these problems would go away. iOS could instantly recognize you were using a trackpad or a mouse, and reconfigure itself accordingly. You’d use that familiar arrow to zip about the screen, editing text, and performing other actions. Your iPad could sit in front of your face, in an ergonomically pleasing position; better, it could mirror its display to a larger monitor, echoing a traditional computing set-up if you also plugged in an external keyboard.

Apple continues to push against this. Perhaps it fears people thinking this would shackle iPad to computing’s past rather than having the tablet define its future. But Apple has always been about combining innovation, picking the best bits from existing technology, and refining the results. Right now, iPad is so close to being a perfect computing device. But in not making the case for the cursor, Apple ensures the iPad continues to be sub-optimal for a range of important everyday tasks it would otherwise be perfect for.